About Regional Realities

Women’s rights and gender equity varies widely across the large, vast region of Sub-Saharan Africa overall. In order for the entire region to move towards further equality, this variation needs to be understood and acknowledged. Within the realm of family, marriage and the household in particular, significant progress has been made over the past fifty years. However, examining results on an aggregate basis can obscure more hidden realities of continued significant gender-based inequality in certain sub-regions. This project dives into these realities to bring them to the forefront. We investigate women’s household agency and norms from a legal-rights perspective, a demographic perspective, and a beliefs-based perspective.

Our Dataset

Using the “Norms and Decision-Making” data set from the World Bank Gender Data Portal, we investigate women’s decision-making capacities in 43 Sub-Saharan African countries with regard to marriage and the household from 1970 to 2022. The expansive dataset draws from three primary sources: the World Bank Women, Business and the Law (WBL) project, Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) compiled by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) implemented under the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

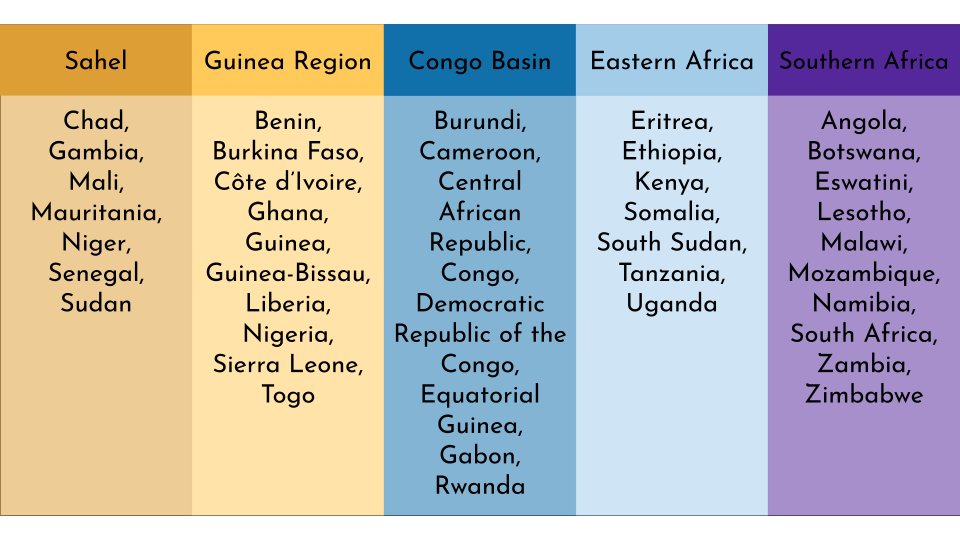

Division of Sub-Regions

The sub-regions that this project analyzes are the Sahel, the Congo Basin, Eastern Africa, and Southern Africa. In organizing Sub-Saharan African countries in this way, we are able to contextualize sub-regional variation within social, political, and economic factors that have either contributed to or hindered moves toward gender-based equality. Perhaps the most common way of categorizing African sub-regions is in terms of cardinal directions: North Africa, East Africa, West Africa, Southern Africa, and Central Africa (University of Pittsburgh). The four latter regions comprise Sub-Saharan Africa. However, this project takes somewhat of a nonstandard approach. We felt it important to highlight the longitudinally-aligned Sahel region, which showed uniformity within itself in a wide variety of indicators. The region is aligned in its semiarid climate and climate-related challenges with desertification and soil erosion, resulting in severe drought in modern history (Encyclopedia Britannica). After noticing this trend, we decided to distinguish the four other regions on a climate basis as well, noticing that this division also correlated with trends in the findings from our dataset.

Our Place in Literature

This project pulls from a wide variety of feminist and empowerment literature, past studies, and data investigations into women’s decision-making, and research surrounding household and family norms in the various countries represented by the dataset.

Our investigation into the significant base of literature on this topic primarily covered three categories of investigation: household decision making splits between husbands and wives, women’s empowerment through education and social change, and literature surrounding marriage and legal rights in the region. One common thread through much of the literature we found based around Sub-Saharan Africa in particular emphasized the paucity of almost every type of demographic data being used. Additionally, almost every article stated that further research, especially cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, are necessary to capture the nuance found in gender equity issues. Importantly, over half of our cited sources performed analysis using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), which are also represented in our data set. As such, the literature serves as a valuable model in our understanding of how such data can be analyzed.

This base is relatively broad, but lacks enough detail to provide a clear window into women’s rights and health on its own. An article written by David L. Chambers provides detail on how only in the past 30 to 40 years have many countries in the region had government reform and been liberated from colonial regimes and apartheid (Chambers 2000). These governments did not aid and often inhibited demographic data collection during their reign and modern data collection efforts require more time to build up a significant corpus. Any data the authoritarian governments did collect at the time were not provided to independent researchers or organizations. The DHS dataset reflects this in the sparseness of data throughout the past half-century. Multiple studies use extrapolation techniques to create estimates that, while more accurate and meaningful than estimates, are still far from depicting the full picture of the period the data was meant to predict. An example of this is singulate mean age at marriage that is extrapolated from the percentage of women aged 40-45 to represent the mean age at first marriage; this is not a perfect technique and only provides some insight into the circumstances of the time.

Despite the low quality of data, though, much of the literature points to the empowerment of women and better outcomes for women’s health and power. For example, child marriage is decreasing thanks to new legislation, and is reflected in demographic data trends and legal review from three studies. Over time, legislation surrounding protections of women’s rights and health has become more comprehensive (Maswikwa 2015). At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that the enforcement of said laws can be difficult to ensure, as many countries lack the economic resources to implement the systems necessary. The literature expresses that women’s empowerment is on the rise overall and slowly penetrating more rural areas, where traditions are more strongly followed. While some studies show that households where women are claiming more power are the most common places for domestic violence, other studies show that many younger women are refusing to accept the violence and that there is lower tolerance for domestic violence towards women.

Importantly, many of these studies emphasize how empowerment has to be tailored to the specific culture and community it is being pursued in; a brute force approach doesn’t create long-term change in attitudes nor outcomes. This is emphasized in Chambers’s article through the description of the balancing act between valuing tradition and enacting progressive change seen in the rise of representative governments in South Africa, where cultures deeply steeped in tradition are exposed to radical change in a short period of time (Chambers 2000). These issues aren’t only present in South Africa, but throughout all of Sub-saharan Africa as every country was subject to colonial pursuit and exploitation. This balanced approach between progressive change and maintaining traditions is important to center in our project’s analysis.